THE SPIRITUALITY OF T’AI CHI CH’UAN

From the T’ai Chi Classics, the T’ai Chi Ch’uan Lun by Wang Tsung-yueh states, “from the comprehension of chin, one can reach wisdom. Without long practice one cannot suddenly understand it.” In the “Thirteen Treatises” by Cheng Man-ch’ing, he elucidates the several different stages of development in one’s practice of T’ai Chi. On the Heaven Level, there are three stages: T’ing Chin (Listening to or Feeling Strength), Tung Chin (Comprehension of Chin), Omnipotence Level. To reach the Omnipotence Level, one must first develop the ability of listening to the chin force of the opponent. From years of practicing push hands, one may develop the ability to comprehend the opponent’s force. In turn, this comprehension comes from your ability to adhere to him and hear when he will he will release his chin force. To comprehend your opponent’s force means to know his slightest movement and where his chin force resides.

The Omnipotence Level is the highest level of achievement in the practice of T’ai Chi Ch’uan and the most spiritual. By spiritual, I mean that the spirit has been cultivated to the degree that it becomes spiritual energy and becomes the primary motivating power for the movement of the body. Cheng Man-ch’ing says, “This stage of enlightenment is difficult to describe.”

Of course, ch’i is the energy that moves the body, but it is the spirit by means of the mind that motivates the ch’i. “The hsin (mind) mobilizes the ch’i”, and “The ch’i mobilizes the body”. “Throughout the body, the i (mind) relies on the ching shen (spirit), not on the ch’i”. This is perhaps the most difficult part of the T’ai Chi Classics to understand unless you have attained it.

Development in T’ai Chi is based on the process of transmutation of energy in the body through one’s practice of the single movements to store and sink the ch’i, and then to transform the ch’i into spirit (shen) by means of the sword practice. At this omnipotence level, the spirit becomes a spiritual force which mobilizes the ch’i to move the body. Since the outward expression of the spirit is through the eyes, “wherever the eyes concentrate, the spirit reaches and the ch’i follows. In turn, the ch’i mobilizes the body. However, because the spirit in the same action carries the ch’i with it, the spirit mobilizes the ch’i and the body at the same time. This is what Cheng Man-ch’ing calls “divine speed”. At this omnipotence level, the body is transformed and can manifest miraculous powers. Hence the Classics describes as the highest level in the body, “If there is no ch’i, there is pure steel”.

It is important to keep in mind that the practice of T’ai Chi Ch’uan is based on Taoism. The ultimate goal of Taoism is longevity or immortality through the harmony of Man with Heaven and Earth. This should be differentiated from the goal of the Buddhist practitioner which is to become enlightened to end the cycle of death and rebirth, and enter Nirvana after all have been saved.

The enlightenment that Cheng Man-ch’ing talks about is an energetic/physical enlightenment by means of the cultivation of the spirit through the transformation of the ching to ch’i, and the ch’i to shen. The application of this transformation is applied to the martial arts.

It is difficult to draw the line between the term enlightenment as it applies to T’ai Chi Ch’uan and Taoism, and enlightenment as it is referred to in Buddhism as they both overlap and influence each other. In Taoism, enlightenment refers to a more material and energetic realm while in Buddhism it refers to the enlightenment of the spirit. Both disciplines are rooted in the practice of emptying the body or emptying the mind as a precondition. In T’ai Chi, you must empty the body of all external strength and relax. As Prof. Cheng often said, you must “invest in loss”. By investing in loss, you are subduing the ego and its manifestation by the nonuse of strength in push hands. In Buddhist meditation, you must empty the mind so there are no past or future thoughts, and no ego. Sometimes it is difficult to empty the mind without first emptying the body and vice versa.

In addition to the practice of “emptying” in T’ai Chi and seated meditation in Buddhism, there is also the similarity of “listening” in both practices. In practicing the single movements of T’ai Chi, you are listening to the differentiation in the body, the parts that are tense, whether the ch’i is sinking, or the inhalation and exhalation. In general, you are listening and following the principles as described the T’ai Chi Classics. In push hands practice, you are listening to your opponent and comprehending where his chin force is. In Chinese Buddhist meditation, you are using listening as a technique in meditation to follow your thoughts into emptiness and then into a spiritual enlightenment. With these aspects of emptying, listening, and subduing the ego incorporated into the practice of T’ai Chi, T’ai Chi Ch’uan can truly be thought of as a form of dynamic meditation.

When I was studying Chinese Zen in Taipei, Taiwan in 1969-70, I participated in a meditation retreat conducted by a famous Zen Master named Nan Huai–chin and who was also one of my T’ai Chi teachers. One of my classmates there was a Harvard graduate student studying comparative religions. She didn’t know much about Buddhism so I encouraged her to attend this retreat. It was a seven-day retreat held across the street from where I lived. There were at least twenty participants and we all meditated facing outwards instead of to the wall. Once in a while during the seven days, I would sneak a peak at the other practitioners to see how they were doing. It was quite a grind to sit for nine hours a day for seven days. On the third day, I glanced over at my classmate and for some reason, she had a big smile on her face. She was beaming. Wow, I thought to myself, she is doing pretty well compared to the pain I felt from the awkward sitting position I was in.

At the end of the seventh day, after the retreat had ended, Master Nan gathered all the participants and announced that a New Buddha had been born. As he announced this, he started to cry with joy and sorrow. He talked about all the suffering that he had to endure to achieve his enlightenment and what others had to go through. He then said that my classmate had the door cracked open just a little to allow her to “see”. From her experience, she explained she now sees the world differently. For instance, when she looked at the painting hanging on the wall, she now saw it totally differently.

That evening, she snuck into my room and asked me for my knowledge of what her experience was. I told her that I understood what she experienced, but that I didn’t feel it like she did. To satisfy my curiosity, I asked her several questions. “Do you love your parents?” She answered that she didn’t love her parents in the usual way that we do, but that she loved her parents in a universal and compassionate way. I then asked her whether she was going to marry her fiancé when she got back to the States. She said no, that she wasn’t in love with him in the way that one would to be married. Wow! To me, this was authentic proof that what she experienced in the meditation retreat was the real thing.

After the retreat, we attended private classes to translate and comprehend the wisdom of the “Tao Te Ching” and the “Sutra of the Sixth Patriarch” with one of Master Nan’s students who was also recognized as someone who was awakened. As the months passed and my departure from Taiwan approached, I watched the body of my classmate go through a dramatic physical change. She had lost a lot of weight and her body reflected her spiritual transformatoin. After I left Taiwan, I never saw her again and I often wondered how her life had changed since her experience with Master Nan.

Enlightenment that is spoken of in T’ai Chi Ch’uan is of the physical/energetic centers of the body that, when applied to the martial arts, give the practitioner an almost super normal advantage. When applied to health, it provides the practitioner with an environment of wellbeing and longevity.

It is widely accepted that cultivation of the spiritual path in Taoism and T’ai Chi Ch’uan is not as high as the spiritual goals of Buddhism. However, the practice of T’ai Chi Ch’uan is a wonderful complement and stepping stone toward the pursuit of the spiritual enlightenment of Buddhism.

“IF THERE IS NO CH’I, THERE IS PURE STEEL”

In the Expositions of Insights into the Practice of the Thirteen Postures of the T’ai Chi Classics, Wu Yu-hsiang states that “The hsin (mind) mobilizes the ch’i.” “The ch’i mobilizes the body.” He later says, “Throughout the body, the i (mind) relies on the ching shen (spirit), not on the ch’i (breath). If it relied on the ch’i, it would become stagnant. If there is ch’i, there is no li (external strength). If there is no ch’i, there is pure steel”. In 1950, Prof. Cheng wrote in his “Thirteen Treatises”, “These words are very strange. They imply that the ch’i is not important, and in fact it is not. When the ch’i reaches the highest level and become mental energy, it is called spiritual power or ‘the power without physical force.’ Wherever the eyes concentrate, the spirit reaches and the ch’i follows. The ch’i can mobilize the body, but you need not will the ch’i in order to move it. The spirit can carry the ch’i with it. This spiritual power is called ‘divine speed.”

In 1934, Prof. Cheng’s teacher, Yang Chengfu published his book, “The Essence and Application of Taijiquan”. It is accepted by the Yang family that Prof. Cheng had ghost written this book. In the Louis Swaim translation of 2005, Prof. Cheng writes in his forward, “In the nautural realm, only by the hardest can one prevail over the softest, and yet it is only the softest that one can prevail over the hardest. The Book of Changes says, ‘Hard and soft stroke each other, the eight trigrams stimulate each other.’ The Book of Documents says ‘The reserved and retiring are subdued with strength, those of lofty intelligence are subdued with gentleness.’ The Book of Songs says, ’Neither devour the soft nor reject the hard.’ If it is so that all of these follow the same principles in the application of hard and soft, how is it that Laozi alone said, ‘In the natural realm, the softest things ride roughshod over the firmest’? And, ‘the soft and weak win over the hard and strong’? I was highly skeptical about this.

At the end of the Sung Dynasty the sage Zhang Sanfeng created the technique of taiji soft fist, with what is called ‘having qi, then there is no strength; not having qi, then there is pure hardness.’

Is this not strange? I felt that this concept seemed even more at odds with Laozi’s theory in particular, and asked, ‘Why is this so?’ I certainly already knew of the softness that comes through not using strength, but had not heard that there was such a thing as not using qi. If one doesn’t use qi, how indeed can one have strength. And then attain pure hardness?

In 1923, I assumed a teaching position at Beijing fine Arts Academy. A colleague, Liu Yongchen, was good at this art of taijiquan. Because I was emaciated and weak, he urged me to study. Barely a month passed before I had to quit because of important commitments, so I was not able to catch on to the art.

In the spring of 1930, because of overwork while establishing the China Academy of Literature and Arts, I had reached the point of coughing up blood, so I resumed study and practice of taijiquan with my colleagues Xiao Zhongbo and Ye Dami. In less than a month, my illness swiftly subsided, and my constitution became stronger daily. From that point on, I practiced day and night with steady efforts. Within two years, when I matched up with men ten times my strength, I caould beat several of them! I was beginning to believe that softness was sufficient to defeat hardness, but still didn’t understand the subtlety of not using qi.

In the first lunar month of 1932, I met Master Yang Chengfu at Mr. Pu Qizhen’s house. After the old gentleman had introduced me, I humbly presented myself at Master Yang’s door, and received his teachings, including his oral instructions of the inner work. I began to understand the meaning of not using qi. By not using qi, I follow the flow, which the other goes against the flow. One has only to follow, then softly yield. The way that softness subdues hardness is gradual, while the way hardness subdues softness is abrupt. Aburptness is easy to detect, and so it is easily defeated. In this notion of not using qi is the extreme of softness. Only the extreme of softness can produce extreme hardness.”

In Barbara Davis’ 2004 translation of the Tai Chi Classics, she gives a translation of Chen Wei-ming’s commentary. “Taiji is carried out purely with the shen and does not set store by exertion. This qi is post-heavenly exertion. Nourishing qi is pre-heavenly qi. The qi of movement is a sort of post-heaveny qi. Post heavenly qi has an end. Pre-heavenly qi has no limit.”

THE FUNDAMENTALS OF MOVEMENT

The T’ai Chi Classics say, “Yung yi pu yung li” or “Use yi (mind/intent), not li (force/strength)”. Many practitioners believe that this applies only to push hands and not the single movements. If this is true, then it begs the question “Is it OK to use muscular strength when you execute the form?” There should not be any distinction made between the single movements and push hands. The correct practice of the single movements is in preparation to the correct practice of push hands i.e. the non-use of force or muscular strength.

So how can you move in the single movements without the use of muscles? Besides shifting of weight, there are two components to the movements, i.e. horizontal and vertical.

Horizontal movement is accomplished by rotation of the hips. The hips are like a wheel lying on its side, and by rotating, it can move the legs and arms horizontally into position like a crane, without activating the muscles. “Stand like a balance and rotate actively like a wheel.” Of course, this means that the vertical axis of the practitioner must be straight and not lean in any direction.

The more difficult practice is the correct vertical movements of the body, or the rising and lowering of the body on the vertical plane. We call this the rising and sinking of the body by means of the “ch’i”. This is a more difficult practice because it is internal. To understand this, you must be able to differentiate the “outer” and the “inner” combined with the differentiation of the upper and the lower. This means you must differentiate the outer body or physical body from the inner body or energetic body.

When most practitioners begin their practice, inner and outer are fused together. This is from their habit of using strength and muscles in their movements and daily life. If I were to practice the external like lifting weights or strength-based exercises that demand a lot of muscular application, I would be fusing the internal and external so that there would not be any differentiation. As a result, my practice of the single movements in T’ai Chi would only be 50% effective. If you watch the demonstration of the single movements of Cheng Man-Ch’ing on video, you can see how his body rises and sinks and that his arms and legs seem to move independently or at a different timing.

For example, in the posture of “White Crane”, you can see his hands and his feet arrive in their final position at different times. If he had no differentiation, his hands and feet would get to their final position at the same time. In his “Raised Hands” posture, the hands and feet also arrive at their final position at a different moment. In both examples, the rising of the “ch’i” or the inner energetic body, is what raises the arms and outer body up. You might also say that inhalation further allows the “ch’i” and inner body to rise, and exhalation aids in the sinking or lowering of the body, such as when you take a step out. If there is no differentiation between the inner and the outer or the upper and the lower, then you are double weighted.

Since the differentiation between the inner and the outer is an internal practice, it is more difficult to cultivate. The first step is to relax all muscular tension and the use of strength. This is a difficult habit to break. It took me over 50 years of conscious practice to break it. The next step is to sink “ch’i” to tan tien. The “ch’i” cannot sink if you are tensed, or if your muscles are not relaxed. If I did 100 sit ups a day and had a six-pack abdomen, the “ch’i” will not sink.

The benefits of the “ch’i” sinking is that everything above it relaxes. The body remains in a healing or parasympathetic mode. Blood pressure drops, blood vessels open up, digestion improves, heart rate drops, breathing becomes deeper and oxygenation better, and circulation of “ch’i” and blood increases.

It is a long process to sink the “ch’i”. It may take years of practice doing the single movements and push hands before it occurs. The greater the differentiation between the inner and outer, the more movement there is between them and the greater the time difference is before the hands and feet reach their final position. This may also be seen when you shift the weight into a 70/30 position. There should be a noticeable time lag in the rotation of the rear foot after the hips have rotated and taken up the slack before the rear foot rotates in 45 degrees. The ironic thing, is that it will look disconnected but it is truly connected by the mind, the “ch’i” and softness.

THE SPIRIT OF THE SWORD

The practice of Tai Ji Chuan is essentially an internal practice of transformation. It is the inner alchemy of the Taoist for refining “jing” into “Qi “ and”Qi” into “shen”(spirit). Each step of the transformation process necessitates long practice and internal achievement to progress to the next level.

The first step of refining “jing”into”Qi” is found in the practice of the single movements of the “chuan”. In it, is the ability to move with deep relaxation and not use muscular strength. This is achieved by emptying the body, sinking the “Qi” to “dan tian” and the transference of the ability to move without using muscles but only the sinews. In this inner environment, the “dan tian” fires are stoked by the solo movements of the “chuan” and the “Qi”is refined and tempered. The single movements are practiced slowly so that the practitioner can pay attention to the relaxation and softness of each posture to refine the “Qi”. In this level, sometimes unusual abilities appear. When I first met Ben Lo, he had the ability to demonstrate the movement of his Qi with each inhalation and exhalation. With each breath, you could see the skin of his hand significantly shift back and forth while completely relaxed and without any muscular activation. He could also place a needle lengthwise along the arm in the crook of this elbow, and flex his arm tightly without the needle penetrating his skin. He rarely demonstrated these abilities because he didn’t want to be mocked by people who couldn’t understand.

In contrast, the Tai Ji sword is practiced fast. Most accomplished practitioners never felt that they were ever ready to learn the sword. When I asked Ben Lo “when did you study the sword”? His reply was “only 17 years after he started studying Tai Ji with Prof.Cheng”. He never felt like he was ready to take up the sword since he didn’t feel proficient enough in the single movements. He was pushed by the Prof. in 1966, to study the sword because he felt that Ben wouldn’t have another opportunity to learn it. (At the time, Ben was living in Taiwan and the Prof. was teaching in NYC.) Ideally, to study the sword, one should have achieved the level of deep relaxation cultivated from the solo movements, sinking the Qi to the dan tian, and the reflex of meeting force with softness. Otherwise, to learn the sword form would be a meaningless choreography. While to practice the “chuan” is to refine the “Qi”, to practice the sword is to transform the “Qi”into “shen” (spirit). Therefore the movements are executed in a quick and lively spirit, and the eyes, being the outward manifestation of the spirit, follow the tip of the sword. Sinking the Qi to the dan tian is the earth, the practitioner is the man and the cultivation of the spirit is the heaven as represented by the trigrams of the I Ching.

PORTALS TO THE SOURCE

When we study a Chinese classical art or discipline we want to be assured we are receiving the most authentic or direct information from the source so that we may practice the discipline at the best and highest level. This has always been a Chinese tradition. With respect to T’ai Chi, those who have had the good fortune to have studied with Prof. Cheng, have had a direct lineage to Yang Cheng-fu, and those who have studied with Ben Lo, have a direct lineage to Prof. Cheng.

Therefore Prof. Cheng and Ben Lo are portals to the source of T’ai Chi Ch’uan at its highest level. When we do our daily practice, we access the spirit and knowledge that have passed through them to reach us in their teaching.

For Ben, Prof. Cheng was his portal to Prof. Yang. For Ben’s students, he was their portal to Prof. Cheng. However even with this direct connection to the source, this does not guarantee that our personal practice will always be correct or that the transmission was correct. We must constantly strive to study the T’ai Chi Classics, question, and re-evaluate our practice to make sure it is correct even if we have practiced for many years or decades.

I remember sometime in the late 1990s, I asked Ben if his shoulder posture was correct. I had taken a picture of him executing shoulder at a demonstration in Taiwan in 1983 with his left wrist straight with the “beautiful lady’s wrist” instead of his hand being bent upward like Prof. Cheng’s and Prof. Yang’s photo. He told me that “it should have been bent and not straight”. So the photo I had taken showing his left wrist of his shoulder posture being incorrect, revealed to me that even after 38 years of practice and having a direct source to the Prof., Ben was still correcting and re-evaluating his movements.

In the recording I made in “Further Conversations with Ben Lo”, he mentioned that the students and his classmates in Taiwan had made photographic comparisons between Prof. Cheng’s posturers and Prof. Yangs’ postures in an attempt to reconcile the differences. I also had tried to reconcile the differences I saw in the postures, but Ben could not give me satisfactory answers.

Another fascinating incongruity occurred when I produced the “Enduring Legacy” video which highlighted the sword form as executed by Ben Lo. It was a sword form which Ben had learned from Prof. Cheng in 1966. Prof. Cheng wanted Ben to seize the opportunity to learn the sword even when Ben felt he wasn’t ready. I believe 1966 was before Prof. Cheng taught the sword form to his American students in NYC. Ben learned the sword form in 4 days and to help him remember the movements, Ben had taken still photos of the Prof. Cheng doing the sword form in his back courtyard.

When you compare the stills with Ben’s sword form, they seem to be quite different, and when you compare Ben’s sword form with the sword form Prof. Cheng taught in NYC and to his other students in Taiwan, it is completely different. In fact, no one had ever seen Ben’s sword form except Ben’s senior students. When I asked Ben why his sword form was so different, his answer was, “Do you think I made this (sword form) up?” Ben had never shown his unique execution of the sword to anyone, not even to his closest T’ai Chi classmates in Taiwan such as Liu His-hung, Chu Hung-bing, or even Robert Smith.

One of the most unique movements that Ben had learned was “The Black Dragon Wraps It’s Tail Around the Pillar” near the end of the form. What Ben displayed in the “Enduring Legacy” video is consistent with what Prof. Cheng taught his other students. However, what Ben learned privately from Prof. Cheng was that there were 6 advancing steps or jumps and no retreating steps in the “Black Dragon” movement. In a martial sense, this movement was designed to cover as much distance as possible to reach an opponent. When I had Ben correct my students’ sword form, he showed these 6 steps but not the jumps.

As a teacher, according to who you teach and the circumstances in which you teach, your teaching methods and content might be different. In Buddhist philosophy, this is called, “skill in means” to assure the student success in becoming enlightened. Could this explain why a teacher will teach differently to some of his students, while other students will sometimes get different answers to the same questions? Some people might think that this is being “very Chinese”. Personal politics aside, what comes from the “horse’s mouth” or the source, might create more questions than give answers. Just as the T’ai Chi symbol is round or circular, it is difficult to get a straight answer.

ELECTRIC PENCIL SHARPENER

In August of 2009, I invited Ben Lo to spend the weekend with me to relax in the country. While relaxing I started to question him further about T’ai Chi and I recorded our conversations thinking that one day they might be of some use to the next generation of practitioners. Recently, I discovered these recordings on my computer which I found interesting not only for its content but also hear Ben’s voice again. His voice is clear and full of energy, and his humor is unmistakable. The audio recordings will soon be available to download.

During his visit, I proudly showed him a new electric pencil sharpener that I just bought from Costco. I told him to stick a pencil in to see how it worked. He followed my instructions, the sharpener activated and started to rotate. As the sharpener began to rotate, the pencil also started to rotate in Ben’s grasp. He said it doesn’t work. I started to laugh hysterically because the pencil could not get sharpened due to Ben’s habit of always being soft and yielding, and never using strength. His grasp of the pencil was too soft, and therefore there wasn’t enough resistance on the pencil against the rotation to be sharpened.

The pencil was left unsharpen.

A TALK GIVEN AT IRI BY MARTIN INN

I’d like to give you an idea about the meaning of T’ai Chi and where it comes from, a brief history of Chinese philosophy. In China and the Far East, medicine, diet, martial arts—everything has its roots in philosophy. In the western world, everything is based on science. There’s a big divide between the two cultures.

The fundamental principle upon which Chinese philosophy is based is one you are familiar with in T’a Chi: Yin and Yang. Where does this concept come from? It comes from the I Ching, the first Chinese classic ever written about, three or four thousand years ago. Many of you know the I Ching as a book of divination, but it’s not really that. It’s the first classic from which other Chinese classics are written. Confucius, Lao-Tse—all based their works on the I Ching.

Let’s look at the meaning of “I Ching”. The character ‘I’ means change, ‘Ching’ means classic. The character for ‘I’ is a combination of two words: the sun and the moon. 日月 Here, we have the principle of two different aspects. There's a dynamic occurring between these two different entities which then were combined. When you look at this character for ‘I’ 易, it looks like some kind of insect. In Chinese concepts, the insect can change its color, it can camouflage itself, like a gecko. The Chinese took this and said the Book of Changes.

All of Chinese philosophy is based upon this dynamic relationship of Yin and Yang. The concept of Yin and Yang was written in the middle section of I Ching called the Ten Wings. if you read the Ten Wings, it’s very profound. I read the Ten Wings, maybe one paragraph of it, for three months, about forty years ago when I was in Taiwan. With my philosophy teacher, I deciphered one paragraph, character by character. Each character had 10,000 meanings behind it. Anyway, this aspect of Yin and Yang covered a lot of territory, but it didn’t cover everything. The theory of five elements came out of it.

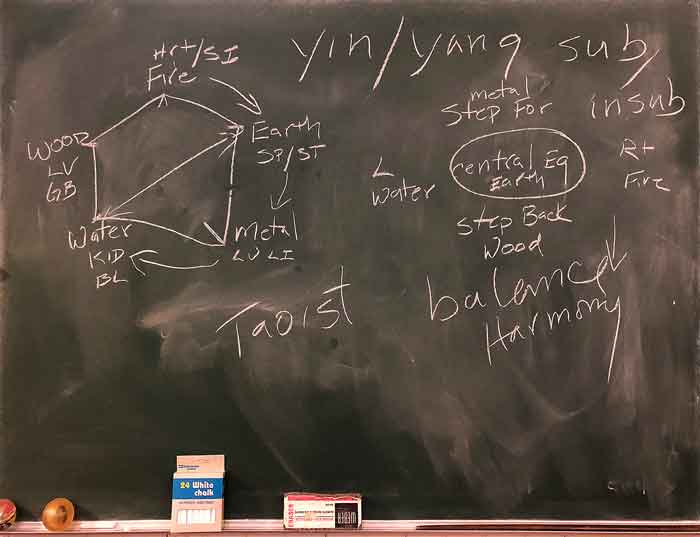

We have the five elements in Chinese Medicine and we have the five elements in T’ai Chi. We have fire, which is represented in our internal organs as the heart and small intestine. We have earth which is the spleen and stomach; we have metal which is the lungs and large intestine; we have water which is kidney and bladder, and we have wood which is the liver and the gall bladder. The heart is a solid organ and the small intestine is a hollow organ. Likewise, the spleen is solid and the stomach is hollow, the lungs are considered solid and the large intestine hollow. The kidney is a solid organ and the bladder is a hollow organ; the liver is the solid and the gall bladder is the hollow organ. The organs being paired off with each element reflects the aspect of Yin and Yang.

We have the five elements in Chinese Medicine and we have the five elements in T’ai Chi. We have fire, which is represented in our internal organs as the heart and small intestine. We have earth which is the spleen and stomach; we have metal which is the lungs and large intestine; we have water which is kidney and bladder, and we have wood which is the liver and the gall bladder. The heart is a solid organ and the small intestine is a hollow organ. Likewise, the spleen is solid and the stomach is hollow, the lungs are considered solid and the large intestine hollow. The kidney is a solid organ and the bladder is a hollow organ; the liver is the solid and the gall bladder is the hollow organ. The organs being paired off with each element reflects the aspect of Yin and Yang.

When you look at the cyclical structure of the five elements, you see that each element generates the next one. Fire generates earth. What does that mean? That means when you burn something, you have ashes; the ashes turn into earth. Earth generates metal. You dig up earth and you get metal, ore. You melt metal and it becomes liquid like water. Water in the earth generates wood. What happens when you burn wood? Ignite wood, it becomes fire. So that’s the generating cycle of the five elements.

How does this translate into T’ai Chi? Well, in T’ai Chi we have Yin and Yang, substantial and insubstantial. We don’t just stand there; we move about. Yin and Yang is a dynamic relationship, not static. The five elements are a dynamic relationship. When we balance in the internal organs, we prevent disease. When they are out of balance, then we have disease occurring: an obstruction, stagnation, or other kind of energetic imbalance.

Dynamic balance is what T’ai Chi is all about. When we shift our weight back and forth, we go from substantial to insubstantial. The binding energy or binding force that bring this all together is your chi. When the chi circulates into the heart, it’s the heart chi. It circulates into the spleen-stomach as spleen-stomach chi. Wherever the chi enters a particular organ, that’s the chi of that organ. The balance is super important. When one becomes deficient or excessive, a domino effect impacts the other organs. They are not isolated. When I treat people who have a heart problem, I like to treat the spleen-stomach. And when I do that, the heart becomes much better.

Each one of these internal organs has an opening to the outside world. The spleen-stomach opening is your mouth. Lungs-large intestine, the nose. Kidney-bladder, the ears. That’s why I say, if you have problems with your ears, I treat your kidneys. Liver-gallbladder what would that be? "Blind drunk. He was blind drunk." You know—alcohol, which effects the liver—the eyes. Because each of these elements and each of these internal organs has a corresponding opening to the outside world, that is the portal in which the inner world and the outer world mix. When you have stress, it comes through one of these portals into your body. Someone screams at you, you hear it. Someone makes a bad gesture towards you, you see it. These things become a permeable membrane between you and the outer world. You’re not a closed system. There’s a dynamic interplay between the inner and the outer.

One organ may control another organ when it becomes out of balance. Water, for example, will control, or be controlled by earth. You can dam up water to control it. Another example: metal can control wood. Think of an axe cutting wood. These are examples of dynamic balance, a very delicate energetic balance inside your body, just like outside the body in nature. When you do T’ai Chi, you have the same type of setup. With wood, you have 'step back’. ‘Step forward' is metal. ‘Look right' is fire. ‘Look left' is water. And see what’s in the center? Earth, your spleen-stomach. The center of all your internal organs is your stomach. Very important.

There are a lot of theories of how to treat organs in Chinese medicine and one of my favorite theories is to always treat the stomach, because it’s a central organ. It is how we get our energy, our chi and blood. If this central function is faulty, every organ will be deficient. These ideas of balance and harmony come from the I Ching, from philosophy, not from science. And yet these ideas play out in both Chinese medicine and T’ai Chi in terms of promoting good health.

Now, the ideas of balance and harmony are not new. We see it in Aikido, for instance. The character for Aikido is 'harmonious chi' or 'the path of harmonious chi'. Everybody wants that. When we do T’ai Chi, we want to promote harmony and balance within our internal organs. And what does that mean with our T’ai Chi practice? One of the most important instructions from the T’ai Chi classics is to sink your chi to dan tien. What does that mean? Why is that so important? It’s a simple phrase, but it’s very important. I think it’s one of the most important phrases in the whole T’ai Chi classics. Because sinking the chi to dan tien means that, by sinking your chi downward, every organ above that sinking level, relaxes.

In my own practice of acupuncture, I see that many people have problems in this area. A lot of people have a pounding pulse an inch or half-an-inch above the navel that is very pronounced. That is from stress. It is an inability to sink the chi below the navel. This prevents chi from gathering and circulating.

In terms of circulation, let’s look at the idea of physical fitness through muscular development. If I were to go through a routine of 600 sit-ups, 400 push-ups, 300 chin-ups, I’d be really buff. Then I’d do my Pilates and work my core - 'solid core’. Buff doesn’t necessarily mean healthy. In terms of circulating chi to promote balance, muscular tension stops the chi from sinking down. The concept of core strength is really incorrect from the point of view of Chinese medicine. Think about this: what happens when you get really stressed and tensed up? Muscles get tense. Having tense muscles all the time, you are practicing your freak-out state, your sympathetic mode, your flight or fight response. Every time you practice muscular tension, you are practicing the flight or fight response.

What does T’ai Chi do differently? It directs us not to use muscles. We try to relax the muscles. Why is this do difficult? Because the instinctive response, particularly to stress and to the outside world, is to tense up rather than to relax. When you have a stress response, you have a strong pulse right above the navel. That’s your inability to sink the chi to below the navel to the dan tien. And a strong pulse here means that all of your internal organs are out of balance, they’re struggling to keep a balance, but it’s an off-balance dynamic. Therefore, when you do your T’ai Chi the first thing I’d like you to do, is to think about sinking your chi to your dan tien. Every movement in the form allows you to practice that sinking aspect. Super important. From squatting single whip to the kicks, whatever, you’re still sinking your chi. And when you do your push hands, that’s a verification of whether you are relaxed or not.

This process of sinking the chi may easily be disrupted by your everyday life. Doing the form is a constant reminder to your body to sink that chi. Just to go through movements has no meaning whatsoever, unless you can sink the chi. To do this, you have to relax your muscles. Very difficult—because of the external forces impinging upon you to keep your defenses up. Rather than to release.

When you do your T’ai Chi, you’re trying to sink your chi to dan tien, you’re trying to harmonize your internal organs through the movements. By doing that, you’re also raising your immune system. You sleep well, you eat well, and things are happy. But, if something is out of phase, then the domino effect will affect every internal organ. So you don’t just fix one thing, you fix many things simultaneously, and this goes for even the fact that if you receive an external injury - that will affect the meridians which will affect the internal organs which will affect all the other internal organs. And of course the most difficult thing to do is to control the mind.

Brain material, according to Chinese medicine, is the same material that goes to make up the kidneys. Isn’t that interesting? The brain stem and the brain is the same—we can’t say genetic in terms of western science—but in Chinese medicine we do say the same genetic material as the kidneys. And the kidneys are the main source of longevity and the immune system.

So take care of your kidneys. If your kidneys are compromised, it will shorten your life, and your immune system will also be damaged. So that’s why I always caution you about this, and I always tell you coffee intake should be watched carefully. Be careful with coffee because it affects the kidneys very strongly, and also affects the heart muscle. The kidneys are considered in Western medicine, the urogenital system. The urogenital system is both your kidney system, discharge of your urine, but also your sexuality. So the loss of sexual fluids is very important for men particularly because that will damage the kidneys if it’s gone too far. So if I’m a sex addict, then that will damage my kidneys. These are very interesting things to look at.

T’ai Chi, with respect to Chinese medicine, has a very important relationship, particularly the sinking chi to dan tien, and the harmonizing of the internal organs. When you open up your arms across the chest, you work the lungs and heart area and the relaxation of the abdomen and the sinking of your chi down opens up everything below. Super important. That’s why I always like to correct you to stretch your arms. By opening up this way, you stimulate the meridians to open up the internal organs.

Chi is the fundamental connection that links all of the elements, all of the organs, everything in your body, and externally. Confucius said there’s an external chi—the great chi of the universe. Well, the inner chi just mimics the outer chi. We think of our internal body as the microcosm of the external world. We can use that as a model, and therefore this inner practice that we’re doing with T’ai Chi is your practice, first of all, to eliminate the use of strength. That’s a difficult one. Two things that really work when they’re linked together: not to use muscular strength and to sink the chi to dan tien. If you get that - these two aspects - you’ve got a tremendous gift from T’ai Chi.

THE AXIS OF T’AI CHI CH’UAN AND CHINESE MEDICINE

The brilliant acupuncturist, Kiiko Matsumoto, in her research into Han Dynasty texts, discovered that the second character, “chi” as found in the name T’ai Chi Ch’uan, means “pole”, and is the same character that is used for “axis”, the imaginary line around which something rotates. If the character is used as a verb, it means “absolute”. In Chinese philosophy and medicine, “absolute” means absolute yin turning into absolute yang as described in the Su Wen chapter 5. An example of absolute yin turning to absolute yang is the phenomena of a hurricane where the eye of the hurricane is still (absolute yin) while the outer winds (absolute yang) is violent and destructive.

In T’ai Chi Ch’uan, this concept is clearly demonstrated in movement. The T’ai Chi Classics state, “Seek stillness in movement”, “Stand like a balance and rotate actively like a wheel,”and “The waist is like the axle and the ch’i is like the wheel.”

In Chinese Medicine, this concept is displayed in the layout of the pulses in the right and left wrists and how they correspond to the internal organs of the body. The spleen pulse is on the rt. wrist while the organ is located on the left side of the body. The liver pulse is located on the left wrist while the organ is located on the right side, opposite to the pulse. The ch’i originates in the lower Tan T’ien and spirals upward to the head in the pattern of the double helix as it circulates through the different internal organs moving from one side of the body to the opposite side. The axis that acts like a pole is the Ren Mai (Conception Vessel) and the Du Mai ( Governing Vessel) which is the same pole in T’ai Chi Ch’uan.

Along with the concept of the central axis or pole in the body, is the axis that the earth rotates around. In Chinese philosophy and culture, the outer world always mimics the internal body, the macrocosmic and the microcosmic. In Han Dynasty times, the world was not thought of as round and rotating around an axis. Their concept of the world was that the Earth was sitting on top of a giant turtle. Instead of an axis there was the North Star, which was central to navigation and a standard which the civilization utilized to oriented itself. The Big Dipper and Little Dipper are arranged in reference to the North Star. Direction is very important to Feng Shui and the 8 Directions are important to the martial arts. The Emperor’s throne was always arranged so that the Emperor faced toward the south and the North Star was behind the throne. In the T’ai Chi sword there is a movement named “South Pointing Compass”. The concept of the North Star being the center, represents something that is quiet and stable. It is still while the other heavenly bodies move in relation to it. In the body, according to Han Dynasty medical texts, the area below Ren 3 is considered to be the North Star of the body. It is the quiet center, or eye of the storm that will influence the rest of the body. The energy that emanates from this quiet center below Ren 3, increases in strength and speed as it reaches the extremities. In T’ai Chi, this is the basis of T’i Fang discharge. In Chinese Medicine, this area below Ren 3 can be a useful point to relieve pain in the hands, fingers, toes, and head. Therefore anything that disturbs the North Star of the body such as C-sections or hernia operations has a negative effect on the rest of the body as the ch’i tries to radiate outward from the North Star. In T’ai Chi to “Sink Ch’i to Tan T’ien” is one of the most important internal practices. It means to gather the ch’i at the North Star. By strengthening the North Star, you can attain better health and longevity. My teacher once told me that Yang Cheng-fu had 3 abdominal operations for obesity. He died after the third operation.

T’AI CHI PRINCIPLES

The Single Movements and Sword Form are just a medium to practice the principles of Tai Chi as expressed in the Tai Chi Classics. The movements have no inherent value without these principles.

STRUCTURAL IMBALANCES IN TAI CHI AND CHINESE MEDICINE

In the history of great masters of T’ai Chi, most of them were not well educated and often illiterate. Prof. Cheng wrote the preface and perhaps the whole classic of Yang Cheng-fu’s “T’i Yung Fa” None of the great masters were trained doctors or practitioners of Chinese Medicine except Prof. Cheng. Therefore the relation T’ai Chi and Chinese Medicine was never clearly understood or how one affects the other. The T’ai Chi Classics state that “the head top should be suspended,” “ the body should be upright to support force from the eight directions” and the “waist is like a millwheel”. This means that the hips must be level at all times or it will not be able to rotate well. If you comprehend the meaning of these three parts of the body, they correlate with the three Tan Tiens. The upper Tan Tien is the suspended head top, the middle TanTien is the up right torso, and the lower or true Tan Tien are the hips and the pelvic girdle. In Tai Chi, the proper alignment of the body of the spine, the hips and shoulders are essential to the correct circulation and internal balance of the Qi. Kiiko Matsumoto, the brilliant acupuncturist and theoretician discovered in her study of the Han Dynasty medical classic, the inner meaning of the ancient Chinese character for the Jen meridian (conception vessel). Since Chinese characters are essentially pictograms, the character of the Jen meridian is actually a schematic of the meridian itself and a code for the treatment of structural imbalance. The character for Jen is made up of three horizontal lines intersecting a vertical line. Kiiko discovered that the vertical stroke of this character represented the Jen meridian which vertically bisects the anterior torso of the body and the lower horizontal stroke represents the “horizontal bone” line just above the pubic bone at K11 ( heng gu), the wider middle horizontal stroke represents“the great horizontal “ line at the level of the umbilicus represented by SP 15 (da heng), and the top sloping line represents the ” horizontal tongue” which is a sloping line that links Du16 at the base of the skull with the tongue at ST9. It was from this discovery that led her to understand the importance of the structural alignment of the body and how it affects the internal organs and circulation of Qi. She discovered that the structural imbalance of the body is not just a physical defect but it also pertains to an energetic imbalance that is created by the physical misalignment of the body. When there is an energetic imbalance, that can lead to many problems in the functioning of the internal organs and their pathways. Some examples of the problems that can arise in the middle Tan Tien are heart diseases such as irregular heart beats, chest pain, anxiety, panic attacks, depression, and hypertension; the problems that affect the lower Tan Tien are usually gastric problems such as poor digestion, mal absorption of nutrients, gas, and abdominal pains such as diverticulitis. The extremities can also be affected and results in arm and leg pains.

There are many factors that contribute to structural imbalances. The main reasons are surgeries on the torso such as C-sections, appendicitis, hernias, tummy tucks, laparoscopic surgeries, gall bladder removals, spleen removals, heart surgeries, spinal fusions, breast augmentation, and lower back surgeries. Even distally located surgical scars on the body at the head or feet can still have a strong effect on the structural balance of the body. I have had patients who have had bunion removals, facelifts, shoulder operations, and head injuries display profound structural imbalances. Another reason for structural imbalances can be related to the alignment of the jaw. If a person has had braces, TMJ, or grinding of the teeth at night, this will reflect in the misalignment of the hips. Strangely, the structural imbalances usually don’t show up until later in life when the Yuan Qi (Original Qi) becomes depleted with age or when other chronic health conditions impinge on the general constitution of the body.

When you practice Tai Chi correctly, according to the principles stated in the Tai Chi Classics, you are employing a form of physical therapy to correct the structural imbalance of the body by suspending the head top (Horizontal Tongue at St 9 and chin), keeping the torso upright (Great Horizontal at SP15), and the hips level (Horizontal Bone at K11).

THE TRIPLE BURNER IN CHINESE MEDICINE AND T’AI CHI

The Triple Burner is often referred to as the San Jiao in Chinese Medicine, and it should not be confused with the three Tan T’iens. There is the upper Jiao which is the chest, the middle Jiao, the stomach area, and the lower Jiao, the lower abdomen. The lower Jiao also happens coincide with the true Tan T’ien. The San Jiao could be thought of as a process of a fire cooking food and the resulting vapor rising from this process to be the essence that nurtures the body. The lower Jiao has what is often referred to as the Tan T’ien fire. The image is that of an ancient Chinese tripod cooking vessel with a fire under it. The middle Jiao , the stomach, is like a steamer with the food in it to be cooked. The fire from the lower Jiao steams and cooks the food, as it is part of the digestion process. The micro essence from the cooked or digested food rises like a vapor to the upper Jiao where it is absorbed and circulated. For this process to be successful, the Tan T’ien fire in the lower Jiao, must be strong to cook the food in the middle Jiao or the result would be poor digestion and a lack of nutrition. Any dietary habit of eating or drinking food that is cold, raw or cooling would put out the Tan T’ien fire and should be avoided. As you can see, the lower Jiao and the concept of the Tan T’ien fire is very important in maintaining ones health. So anything that would stoke the true Tan T’ien fire in the lower Jiao such as the practice of sinking the qi and the cycling of the hips in T’ai Chi makes the digestive fire stronger and the health better.

THE Magic Of T’ai Chi

The way I practice and teach T’ai Chi is the same way I practice acupuncture, there has to be magic. Otherwise it is stale and without inspiration. It has no life.

THE IMPORTANCE OF THE tan t’ien IN T’AI CHI AND CHINESE MEDICINE

One of the most important phrases from the T’ai Chi Classics is, “Sink chi to tan t’ien”. We talk a lot about the tan t’ien in the martial arts and Chinese Medicine, but little is known of it. The first mention of the tan t’ien is in chapter 8 of the Nan Ching, the Han Dynasty classic of Chinese medicine. It talks about the “space between the kidneys that vibrates”. It didn’t call it the tan t’ien but was later given that name by the Taoist, who were the scientist in ancient China. There are three tan t’iens. The upper tan t’ien is located between the eye brows and is referred to as the “spiritual tan t’ien”. The second tan t’ien is located in the chest between the nipples and is considered to deal with the emotions. The third tan t’ien is the lower tan t’ien, which is located in the area below the navel and is considered to be the “true tan t’ien”. The true tan t’ien is linked to the kidneys, the brain, the adrenals and the immune system. The Han Dynasty Chinese medical practitioners believed that the true tan t’ien was like a map of an inverted head where the nose was represented by the navel, the eyes to the side at ST25, and the brain in the lower abdomen at CV3. Because of these associations, the tan t’ien is further linked to ones longevety, the bones and the building of blood, and ones sexuality and libido.

With respect to T’ai Chi Ch’uan, the first internal martial exercise is to “sink ch’i to tan t’ien”. This action is to accumulate the ch’i and fortify the tan t’ien. As a therapeutic function, this tonifies the kidneys and adrenals, strengthens the immune system and bones, and fortifies the sexual organs. In T’ai Chi all movements must originate from the tan t’ien. This means that with the shifting of the weight and the rotation of the pelvic girdle, the movements move outward like concentric circles to the arms and legs giving us the characteristic coordinated movements of the postures. The three aspects that make the tan t’ien powerful, are the sinking of the ch’i, the rotation of of the pelvic girdle which stimulates the acupuncture points, and the shifting of weight which acts like a pump to circulate the ch’i.

I often say to my students that when you practice T’ai Chi Ch’uan, you are giving yourself an acupuncture treatment. More specifically you are giving yourself a tan t’ien treatment.

Because of its importance in Tai Chi Ch’uan, we should really call it Tan T’ien Ch’uan.

HOW FAST SHOULD YOU DO THE SINGLE MOVEMENTS?

This is a question that is often asked from beginners who are not sensitive to their internal world. They just learn the movements and follow the speed set by their teacher. However for the beginner, this may not be the correct speed of doing the form according to their stage of development. When I first leaned the form, I noticed that I was doing the form a lot faster than my teacher. As I watched my teacher do the form, it seemed like his shirt was rippling whereas my movements did not have this kind of flavor. I realized the difference was that my teacher had a lot more changes in his movements than me, and that is why he would take a longer time to execute the form. Through the years of practice, and the cultivation of greater relaxation, my movements began to take on the flavor of my teacher and his changes. Not only did it take longer for me, I had to simultaneously pay attention to more parts of my body as I executed the form.

So what determines the speed of doing the form? At one time, I thought that the slower I did the movements, the more I got out of it. However I discovered that by doing it too slowly it caused stagnation. On the other the hand, doing it too fast did not allow the body to relax and just promoted more muscular tension. Then I thought that the breath would be the central factor in determining the speed of execution. One would coordinate the inhalation and exhalation with the movements. This concept is not incorrect however it didn’t go deep enough. On the inner energetic level, the speed of the movements should depend on the rising and sinking of the Qi. What governs the timing of the shift of weight from one leg to the other is the sinking of the Qi into the feet. As the Qi rises, the weight can begin to shift from the substantial leg on to the insubstantial leg. If the Qi has not reached to the bottom of the substantial leg and the practitioner begins to prematurely shift the weight, the movement becomes uncoordinated and external. This is the lack of coordination of the internal and the external and can result in being double weighted. So the cadence of the single movements should depend on the rising and sinking of the Qi. This is also matched by the inhalation and exhalation of the breath. The rising of the Qi is more easily achieved by an inhalation and the sinking of the Qi an exhalation. This is also matched by the rise and sink of the external body in the movements. In the beginning, the student is taught that the form should be executed so that the body moves on one level plane. However, as the practitioner develops more of the internal, he begins to feel that the body naturally rises and sinks with the inhalation and exhalation of the breath, and it also naturally matches the rising and sinking of the Qi in the internal body. The more practiced the student becomes the deeper the Qi sinks and the more changes he has in the movements. When your Qi sinks into the feet, you will also develop root. This requires years of dedicated practice. The 37 movements short form should take about 8 minutes to execute. (see my thoughts on “Sinking the Qi”, Oct. 1, 2014)

Seeking the Upright Posture

The Tai Chi Classics states, “The upright body must be stable and comfortable to be able to support force from the eight directions”. In the “Lun”, the Classics further state, “Don’t lean in any direction”. Many practitioners have no idea of what the Upright Posture means and so their practice becomes a futile attempt to become internal. There are three things to pay attention to when seeking the upright posture. 1) “Sink the chest”. This means the chest ought to be relaxed down but not caved inwardly. When this occurs, the diaphragm relaxes and in turn allows the “Qi” to sink. As the chest relaxes downward, then you can do abdominal breathing. 2)“Sink the Qi to Tan Tien”. This means that the abdomen is so relaxed that the energy sinks below the navel with the dropping of the center of gravity. This gives you greater stability and root. 3) “In moving, the Qi sticks to the back and permeates the spine”. This is one of the most difficult aspects to practice since it depends on the two previous conditions. When the Qi sticks to the back, the lower back becomes straight and relaxed with no sway in it at all. In other words the Qi fills up the lower back. What happens is that the abdominal breathing begins to appear in the sides and lower back just below the kidneys. Instead of the inhalation and exhalation movements occurring in the lower abdomen, it appears to the side and lower back. The Qi circulates to the back via the Dai Mai meridian, which is the only meridian in the body that runs horizontally and not vertically. With the Qi running to the lower back, it stimulates the kidneys which holds the immune system of the body as well as ones longevity. When the back is straight, the sacrum and coccyx will naturally drop under the torso. It would be grave mistake to tense up the abdomen in order to achieve this. Practitioners sway their back for one reason, their legs are too weak to support the body and by swaying the back it takes the pressure of the thighs. In the long run this will cause damage to the knees.

When all three conditions are fulfilled, the body is put into a position which will promote it to be in a parasympathetic mode. This is the healing aspect of Tai Chi. Each of these three steps will take time to develop and can not be achieved in a couple of years.

History of Tai Chi

If you are interested in the history of Tai Chi, and especially the Cheng Man-ch’ing lineage, I recommend that you go to the Via Media website and buy the ebook on the Professor. These are all the articles that were written and published in the Journal of Asian Martial Arts. The book gives a wonderful insight into who Cheng Man-ch’ing was and how he developed the form of Tai Chi that we practice today. There are a number of interesting stories and facts about that I had not known.

Remember

Li (external force) comes from the muscles and bones.

Chin (internal energy) comes from the sinews.

internal martial arts

Many people talk about the internal, internal exercise, or the internal martial arts but few have any idea of what they mean. A visitor came to our school the other day because he told me that he was interested into the internal martial arts and he wanted to study Tai Chi. When he came to visit, he walked into the school, paused at the door, did a semi bow, took off his shoes, and sat down to watch the class. He watched us do the warm up exercises and the form intently for the first several minutes, and then he took out his mobile phone and spent the next 10 to 15 minutes looking down at it.

In the middle of the second round of doing the form, he quietly got up and walked out. While doing the form, I couldn’t stop laughing inside because I knew that he had no idea at what he was looking at. He must have had a previous concept of what the internal exercise was but when he saw us doing the internal exercise, i.e., the form, it did not match up to his expectations.

So the thought became apparent to me that most people do not understand what internal exercise means.

In Chapter 4 of “Cheng tzus’ Thirteen Treatises on Tai Chi”, Prof. Cheng talks about two things that comprise the Internal: mind and Qi. Internal exercise means the exercise of these two aspects of what makes up the internal body. It is internal because it is not part of the physical body. The physical is easy to regulate because it is material. The mind and the Qi are difficult to regulate because one is energetic and the other mental, and they can not be easily controlled or manipulated.

The Tai Chi Classics state that “The mind mobilizes the Qi, and the Qi mobilizes the body”. In motion, the mind initiates the action and the Qi becomes the medium through which the body is brought into action. If we examine this process carefully, it is evident that this must take a kind of meditative process in order to make this happen. This process is the control of the mind to join with the Qi to a motivate the body to a particular action.

The first internal exercise, in Tai Chi is to “sink the Qi to tan tien”. This may not be as easy as it seems. Many practitioners, who have practiced Tai Chi for many years, still can not do this simple exercise. This first step is also a fundamental exercise in many forms of meditation.

The phrase, “contemplate your navel”, which is often used to refer to meditation, is none other than “sink Qi to tan tien”. Since this is an internal process, it is difficult to assess whether you have been successful or not. It is not a sudden accomplishment but a slow and gradual process that will take many years of deep relaxation and practice of the single movements.

Many students have mentioned to me that their trainer, health practitioner or physical therapist have told them that they need to “strengthen their core” to become more healthy. This is a concept that probably came from Pilates. According to my understanding of health and Tai Chi, this is the most contrary idea to the development of the internal practice. I see it in just the opposite way. I say “you must develop your 'core relaxation’”. In order to sink the Qi and circulate it throughout the body, the muscles must be totally relaxed and not obstruct the flow.

To know whether you have been successful or not, you must test your softness and root in push hands practice. If practiced correctly and with patience, your softness and root will continue to grow through the years. This is why when someone tells me they want to study Tai Chi, I sometimes roll my eyes and say to myself, “you have no idea what you are getting yourself into.”

So I encourage you to come to class as often as possible to continue to nurture your softness and root.

T’ai Chi Lun

The “T’ai Chi Lun” states, “Stand like a balance and rotate actively like a wheel” and the “Expositions of Insights into the Practice of the Thirteen Postures” states, “The upright body must be stable and comfortable to be able to support (force from) the eight directions”. Both of these statements indicate that the body must be upright and not lean in any direction. In terms of health “why is this so important?” In a form of acupuncture that is practiced by Kiiko Matsumoto, an innovative and brilliant acupuncturist, the alignment of the body must be perfect so that the Conception vessel or Ren and the governing vessel or Du meridians, that separates the left and right sides of the body, are not misaligned. The Ren meridian starts at the root of the tongue and goes down the front of the body to the perineum. The Du meridian starts at the base of the skull and goes down the back of the body to the anus. The tongue connects the Ren and Du meridians so that there is a connected circuit. If there is any misalignment or disturbance of these channels e.g. surgeries or injuries, Qi stagnation will occur, and the circulation of Qi will be compromised. Many different health conditions can occur from this misalignment, that will affect not only the torso, but also the limbs and head. Kiiko discovered that many distal problems of the body, such as ankle pain, knee pain, headaches, carpal tunnel pain, shoulder pain, or even lower back pain, can be cured by re aligning the body so that the Ren and Du meridians are straightened and then the yin and yang energies of the body can be balanced. This re aligning of the body means that the hip must be level, the shoulders level and the head top be suspended. Through her research in the ancient Chinese Medical Classics, Kiiko discovered that the ST9 acupuncture points in the neck is called the “Horizontal Tongue”, the SP15 points that are lateral the navel are called the “Great Horizontal” and the points above the pubic bone, K11 are called the “Horizontal Bone”. She found that by using these points, she could re align the Ren and Du meridians and thus begin to cure many health conditions of the body. With the perfect upright posture, and the head top suspended, the hips at SP15 and K11 act like a balance or scale and can easily rotate like a wheel. With this perfect balance and alignment there is no double weightiness in the circulation of Qi throughout the body. This is why practicing the form and forming the habit of not leaning, can not only lead to better health but also having the advantageous position in the martial arts and life.

Tai Chi Classics

When I first began my study of Tai Chi over 45 years ago, I was a graduate student of Chinese Philosophy at the University of Washington in Seattle. I read the Tai Chi Classics and I was astounded at how the principles of Tai Chi and the underlying ideas of Chinese Philosophy were identical. I felt that by practicing T’ai Chi one can actually and physically recreate Chinese Philosophy in ones own body. In other words, Chinese Philosophy became a living entity instead a bunch of abstract notions in a difficult to decipher text book. The idea that one could actually feel and manifest Chinese Philosophy, and yes, even breathe it, became an exciting concept. Recently, while teaching a push hands class, the concept of the Tao came back into focus. We can become like theTao by manifesting its qualities in our practice of T’ai Chi. The Tao is “mysterious”, “soft and yielding”, “feminine”, “The Mother”,“empty”, and “powerful”. When we practice push hands, we practice stealth by being soft and being mysterious. We “suddenly appear”, and we “suddenly disappear.” “The opponent doesn’t know me, I alone know him.” “Being still, when touched (by the opponent), be tranquil and move in stillness; (my) changes caused by the opponent fill him with wonder.” The Tao is soft and yielding. In push hands, “The softest will become the strongest”. Push hands should have the soft but powerful qualities of water. The T’ai Chi Classics say, “Ch’ang Ch’uan is like a great river rolling on unceasingly.” “Be as still as a mountain, move like a great river.” In push hands, “When the opponent is hard and I am soft, it is called tsou (yielding).” “Originally it is giving up yourself to follow others.” The Tao is feminine and the Mother of all. “T’ai Chi comes from Wu Chi and is the mother of yin and yang.” When we empty the mind and body of all strength and ego, we practice the yin or receptive qualities of the Tao; we yield and become the emptiness which is its function. The T’ai Chi Classics says that in push hands, we should “Attract to emptiness, absorb, and discharge.” By continually practicing and manifesting these qualities in our push hands, we can imitate the Tao and we can understand what the ancients were seeing. We can see that human nature hasn’t changed much and what was important then is still relevant today. Therefore the Tao no longer remains just a philosophical concept but by our practice of T’ai Chi, the principles of the Tao can become a practical strategy for living today.

“WALK LIKE A CAT”

Most practitioners of Tai Chi think they understand what this phrase from the Classics mean; however they do not practice it. When they take a step in the single movements, the step is clumsy and double weighted. I have seen “masters” and advanced students with many years of practice stumble about and break their alignment when they step out during the execution of the form. Here is their mistake. When they take a step, say from ward off left to ward off right, the practitioner juts out the right hip in order to push the right leg outward to take the step. At this moment the right hip is tensed and thrown out of alignment with the spine; so for a split second you are double weighted. Not only is the hip thrown out of alignment with the spine, but in this case it is raised to pick the leg up for the step. This contradicts the Classics which says that the hips must be level at all times. The remedy to this is counter intuitive. When you take a step, you must sink the insubstantial hip in order to facilitate the stepping leg to raise. This allows the foot to float up and the hips to remain level. When you place the foot down the hips and spine are in perfect alignment and the step is like that of a cat. Of course this is all predicated on the fact that you are 100% on the substantial leg and you remain 100% until the insubstantial foot is placed on the ground. You will feel relaxed and have a sense that you have all the time in the world to take that step.

REAL ROOT OR FALSE ROOT?

In push hands, when you encounter a partner who is really grounded and is difficult to push out, you often attribute this to his having good root. In my experience this is often not the case. He is just experienced enough to use his leg strength to resist your push and at the same time, your push is too hard (you are using too much muscular strength to push). To over come this situation, you must quickly release your push to see if your opponent falls forward. This means that he is bracing against your push by pushing back against you with his strength. I call this “leaning Qi”. This ends up to be a “double weighted” condition where force meets up with force. True root is when the body is empty of all strength so that it could receive the force of the opponent and channel it to the ground. False root is when the body is full of strength to push back against the opponent’s push at the moment of his push. If you are one of these practitioners who use leg strength to push back, do not despair. If you recognize that you are using strength, this is a steppingstone to realizing real root. All you have to do is have confidence that you can empty the body and still have real root to respond to the “eight directions”.

WHAT QUALITIES SHOULD GOOD PUSH HANDS PRACTICE HAVE?

In practicing push hands, there should be softness, sensitivity, lightness, and liveliness. Unfortunately the majority of push hands practitioners tend to be heavy handed and hard. In yielding, they use more than “four ounces to deflect a thousand pounds” because this is due to their lack of sensitivity in listening and interpreting. When they finally comprehend what to do, it is too late to be effective. The practitioner ends up wiggling about; hoping to neutralize by chance. In pushing, if they can’t topple the opponent with a light push, then they often make the mistake of continuing with the same technique by using force instead of changing to another attack or direction. To develop the sensitivity, you must practice with someone who has softness and a light touch. Lightness means that your “ch’i” is not committed or leaning in any direction, and it is ready to respond to force from all directions. This will lead to liveliness and quick responses on your part. “It is said, If others don’t move, I don’t move. If others move slightly, I move first.” Remember, a slow response or a lack of response is stagnation and resistance. It is also a reflection that the spirit is not raised and is a kind of depression of the “ching shen”. The sensitive, light, and lively practice has a very beneficial effect on the health. It causes the “ch’i” to be active and stimulated, and the circulation of “ch’i” and blood to be full. This light and lively practice can also benefit the spirit. The T’ai Chi Classics say, “The Ch’i should be excited, the shen should be internally gathered.” Students often laugh and giggle while practicing in this manner. A good push hands practice should raise the spirit, lift the mood and promote a playful exchange.

“Qi”

By congesting the “Qi”, it is meant that the Qi gets locked up in the muscles because the muscles are utilized in the exertion of strength or “li”.

Using strength in push hands

Using strength in push hands is promoting a kind of stagnancy in the body by congesting the “Qi”.

WHAT HAPPENS WHEN YOU DO THE SINGLE MOVEMENTS?

Whenever I watch people do the form, I can see directly into their cultivation of “Qi”. In the beginning the form looks crude and without grace. The steps are clumsy, the arms look stiff, and there is no flexibility in the body. When the body moves, big sections of the body are stuck together and there is a lot of stagnation. This is the exact reflection of the inner state of their “Qi”. The “Qi” is like raw or crude metal that has not been tempered and refined. However as the years go by and the body relaxes, the form becomes more smooth, more elegant, and more refined. The steps are smooth and empty, and the body seems as if it has no bones. This begins to reflect a more refined state of the “Qi”. The “Qi” mobilizes the body and it easily follows the direction of the mind. There is excellence of roundness and smoothness and it is nurtured without harm. The “Qi” moves as in a pearl with nine passages without breaks and spreads throughout without hinderance, so that there is no part of the body it cannot reach.” Practicing the form everyday is gathering, refining and tempering the “Qi”. This is the inner practice of T’ai Chi.

SPEED IN T’AI CHI

When you first watch T’ai Chi being practiced, it is a slow, deliberate, set of movements, and you wonder how can this be an effective martial art? It isn’t until you practice push hands, will you understand how fast and quick it is. The speed of T’ai Chi is not in how fast you can move, but it is the reality you have already gotten to your opponent before he can move. It is what the T’ai Chi classics mean when it states that you should “move last but arrive first”. This is achieved by always maintaining the “advantageous position” with respect to your opponent. By doing so you are always there before he realizes it. Whether you are yielding back or moving forward, you are always juxtaposing yourself into the advantageous position and you are never vulnerable. If you are at the finish line, is there any need to hurry? If you are not there, you will always have to play “catch up” by trying to move fast. This is not the real T’ai Chi.

San Shou

San Shou is a 2-person exercise that teaches the application of T’ai Chi movements in a continuous and flowing form. The movements are separated into Side A and Side B, with each side responding to the other’s attacks using a T’ai Chi movement from the single form. It is considered one of the most advanced practices of T’ai Chi Ch’uan because it not only teaches application but also how to step and coordinate with an opponent while maintaining softness and adherence in close contact.

MUSCLES VS. SINEWS

Whenever you study with a good T’ai Chi teacher, the frequent admonition is to relax. From Yang Cheng-fu, to Cheng Man-ch’ing, to Ben Lo etc., the idea to relax the muscles of the body and the mind is the most fundamental principle to practice. What is the teacher really saying when he says to relax? He is saying “do not use the muscles when you practice”. How is this possible? If you don’t use the muscles, then how do you move? How do you stand and remain upright? This responsibility is placed on the sinews of the body, the connective tissues that attach the muscles to the bones at the joints. The transition from the use of muscles to the use of the sinews is a very long and gradual process, and is not accomplished overnight. This transition has taken me over 40 years to understand and then to begin to realize. We can make a simple equation. The use of muscles equals external and the use of the sinews is internal. Whenever we use muscles to push, the force is hard and brutish. Whenever we use the power of the sinews, the feeling of the power is soft and gentle. It comes from a deeper place of the body and utilizes the complete body to manifest. The force from the use of the muscles usually comes from the local source of the body such as the arms and shoulders, and it is short and narrow in scope, easily detected, and quickly neutralized. The power from the sinews is long,broad and soft, and more difficult to detect and neutralize. When we give up the use of our muscles, we become more sensitive and our “listening chin” is more acute. When our muscles relax, we can respond more quickly and our movements become fast. We move last but arrive sooner. Being more internal, our movements become smaller and less externally detectable. The power of the sinews is much stronger than external muscular strength. When we use our muscles, there can be a double weighted condition in the limb where one set of muscles work against another. For example, if we tense up the muscles of the upper arm, the biceps will work against the tricep muscles and diminish the power of the whole arm.

Often the use of strength is tied up with our ego and the fear of loosing. This is the reason Prof. Cheng used the phrase, “invest in loss”. We must give up boosting our ego and then we will give up the use of strength and our muscles. Only then will we succeed in switching over the use of muscle power to the use of sinew power. This can be a kind of spiritual practice and a meditation of the physical body that ultimately reaches the “shen”. How about it?

T’ai Chi movements are circular

I was discussing the single movements with Ben Lo one day and how the principle of T’ai Chi movement is the circle. All T’ai Chi movements must be circular. Then I started to narrow down the postures to see if there were any movements that were not circular. I ventured to say that “double push” was not circular and perhaps “shoulder”. He said “you are wrong.” There are only two movements that are not circular, “double push” and “beginning Tai Chi”. All the other movements are circular. (By circular, we mean that the hips rotate when you shift the weight.) So what does this mean to our practice? It means that in every moment of our movements, when we shift the weight, the hips must simultaneously rotate. Many advanced practitioners do not do this. They normally shift the weight then rotate the hips at the end of the movement but not simultaneously. Of course this is more difficult to do because you must be aware of doing several things simultaneously or together. I have found that this leads to a more effective reaction response in push hands because you are able to listen and respond to many directions at once because of the practice of being able to do multiple things at the same time. This also is more powerful because of the acceleration of the energy in the circular movement.

“WHAT DOES IT MEAN TO BE DOUBLE WEIGHTED?”